Your SOC 2 auditor asks: "Show me your documented access review policy."

You hand them a 2-page document your predecessor wrote in 2020. It states: "User access to systems and applications will be reviewed regularly by appropriate personnel to ensure access remains appropriate."

The auditor highlights three phrases: "regularly," "appropriate personnel," and "remains appropriate."

He asks: "What does 'regularly' mean—quarterly, annually, continuously? Who qualifies as 'appropriate personnel'—managers, application owners, security team? How do you define 'appropriate' access—least privilege, role-based, business justification?"

You realize your policy is so vague it's meaningless.

The auditor notes: "Without specific requirements, I can't determine if you're following your own policy. This will be documented as a control deficiency."

Your vague policy just created a compliance finding.

The Vague Policy Problem

Auditors cite inadequate policy documentation in roughly one-third of access control findings.

Vague policies create compliance gaps because they establish no clear requirements. Over-specific policies become outdated quickly and require constant revision.

The balance: specific enough to be enforceable, flexible enough to remain relevant.

This is what IT Operations teams struggle with:

- Too vague: "Access will be reviewed regularly" → auditor asks "how regularly?"

- Too specific: "IT will log into each application admin panel and export user lists" → breaks when you implement SSO

- Just right: "Access reviews occur quarterly for financial systems using automated discovery methods, with manual export for legacy systems"

We've helped 200+ mid-market companies (500-5000 employees) document their access review policies for SOC 2, ISO 27001, SOX, and HIPAA audits.

In this article, we'll show you what to document in your policy to pass audits—the 8 essential components, why each matters, and how to customize for your organization.

What Is an Access Review Policy?

An access review policy is compliance documentation that defines your review framework for auditors.

It answers:

- Who reviews access (roles and responsibilities)

- What gets reviewed (scope and systems)

- When reviews happen (frequency and triggers)

- How reviews are conducted (methodology and criteria)

- Why certain decisions are made (compliance drivers)

- Where evidence is stored (audit trail and retention)

What it's not:

- A step-by-step execution guide (that's your procedure)

- A high-level workflow diagram (that's your process)

- A training document for reviewers

Think of it as: The contract you're making with auditors about what you'll do and how you'll prove it.

Why Most Policies Fail Audits

Before showing you the 8 components, here's why most policies fail in practice.

The Policy-Practice Disconnect

Your policy says: "User access will be reviewed quarterly."

Your reality: IT spent 30 days last quarter just gathering current access data from 95 applications before reviews could even start.

Week 1: Manually exporting user lists from each application. Week 2: Chasing down app owners who didn't respond. Week 3: Normalizing data formats. Week 4: Discovering some exports are already 30 days stale, requiring refresh.

Your policy doesn't address HOW to discover current access state—just that reviews must happen quarterly. The policy assumes you can start reviews immediately. Reality requires a month of data archaeology first.

The fix: Don't write requirements you can't execute.

If you don't have automated discovery covering all applications, your policy shouldn't promise quarterly reviews of "all systems" starting day one.

Instead, specify quarterly reviews for "SSO-integrated applications" and annual reviews for "applications requiring manual data extraction" until you build better discovery.

Match policy to current capability, then update policy as capability improves.

The Remediation Fantasy

Your policy says: "Inappropriate access will be revoked within 5 business days."

Your reality: 73 access violations identified in Q2 reviews. Six weeks later, 40% still have active access.

Not because IT ignored the policy—because 32 of your 60 applications aren't behind SSO and require manual admin panel login to revoke each user individually. Some apps don't have admin panels at all, requiring vendor support tickets that take 5-10 business days just to acknowledge.

Your policy didn't account for applications without API integrations. It assumed instant revocation was technically possible. It isn't.

The fix: Your policy should acknowledge remediation complexity.

Instead of blanket "5 business days," specify "5 business days for SSO-integrated applications, 10 business days for applications requiring manual revocation."

Better yet, include in your policy a commitment to integrate high-risk applications with SSO over the next 12 months, with specific milestones.

This transforms your policy from wishful thinking into a roadmap.

The Perfect-Looking Policy

One healthcare company had an immaculate 12-page access review policy covering SOX, HIPAA, and SOC 2 requirements before they started using Zluri. Beautiful policy documentation. The auditor loved it during the readiness review.

Then the actual audit happened.

The auditor asked: "Show me evidence of quarterly reviews for your financial systems."

The company produced spreadsheets from October showing certification decisions.

"These spreadsheets show reviews occurred, but where's the evidence that revocations actually executed?"

They had Jira tickets marked "complete" but no validation testing.

"Your policy requires audit trails, but I see email threads, Slack conversations, and scattered Jira tickets. Where's the unified evidence system your policy describes?"

They spent 8 hours compiling evidence from five different systems into a ZIP file.

Their policy looked perfect. Their execution was poor. The policy promised capabilities they hadn't built.

The lesson: Your policy should describe what you actually do or what you're committed to building, not aspirational capabilities you hope to have someday.

If you don't currently have automated evidence collection, don't write a policy requiring it—instead, write a policy requiring manual evidence collection with specified format and storage location, PLUS a commitment to automate within X months.

Auditors respect honest documentation of current state plus improvement plans more than perfect-looking policies contradicted by reality.

The 8 Essential Access Review Policy Components

A complete user access review policy includes eight essential components. Missing any section creates compliance gaps or operational confusion.

Each component below explains:

- What it is: The component definition

- Why it matters: Impact on compliance and operations

- Common mistakes: Where teams go wrong

- Customization factors: How to adapt for your organization

Component 1: Purpose and Scope

What It Is

This component defines why access reviews exist and exactly what they cover. It establishes the boundaries—what systems, users, and access types fall under your review program.

The purpose statement connects reviews to business outcomes (security, compliance, efficiency). The scope definition creates an explicit list of in-scope systems, users, and access types—plus what's excluded.

Why It Matters

For auditors: Scope determines what evidence they'll request. If financial systems are in-scope, they'll ask for review evidence. If you claim "all systems" but only review 40%, that's a finding.

For IT Operations: Clear scope prevents arguments about whether something should have been reviewed. "Is our test environment in scope?" "Let me check the policy... no, section 1.2 explicitly excludes test environments."

For budget: Scope drives tooling and resource requirements. Reviewing 20 critical apps requires different investment than reviewing 80 apps across the organization.

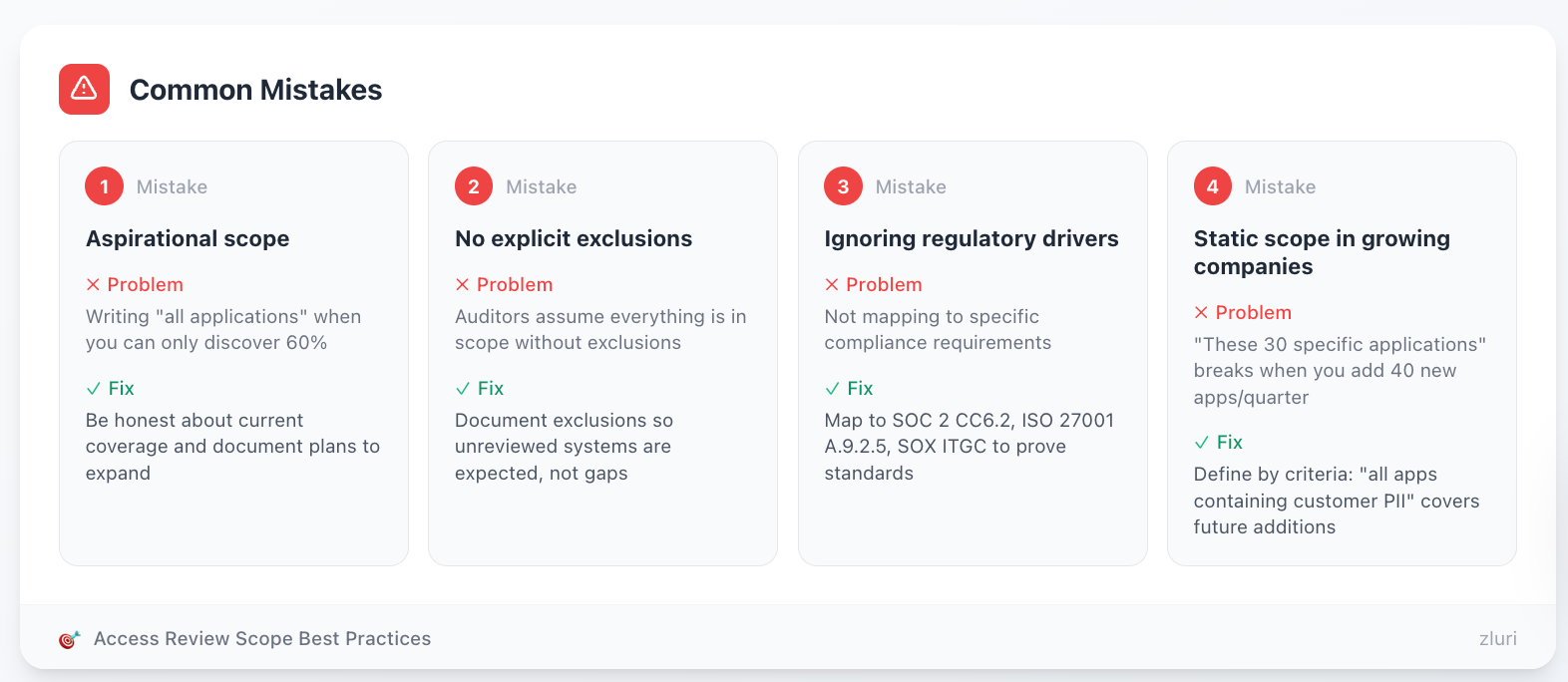

Common Mistakes

Mistake 1: Aspirational scope Writing "all applications" when you can only discover 60% creates instant non-compliance. Be honest about current coverage and document plans to expand.

Mistake 2: No explicit exclusions Without exclusions, auditors assume everything is in scope. When they find unreviewed systems, it becomes a gap instead of an expected exclusion.

Mistake 3: Ignoring regulatory drivers Not mapping to specific compliance requirements (SOC 2 CC6.2, ISO 27001 A.9.2.5, SOX ITGC) makes it harder to prove you're meeting standards.

Mistake 4: Static scope in growing companies Writing scope as "these 30 specific applications" breaks when you add 40 new apps every quarter (all tech companies). Define scope by criteria instead: "all applications containing customer PII" automatically covers future additions.

Customization Factors

By company size:

- Small (<500 employees): Start with critical apps only (10-20 apps). Annual reviews acceptable for low-risk.

- Mid-market (500-5000): Tiered approach—quarterly for critical, semi-annual for standard, annual for low-risk.

- Enterprise (5000+): Monthly reviews for highest-risk, sophisticated role-based access requiring continuous certification.

By industry:

- Financial services: Must explicitly scope SOX systems, emphasize segregation of duties, shorter review cycles.

- Healthcare: HIPAA scope mandatory (ePHI systems), role-based access tied to minimum necessary standard.

- Tech/SaaS: Focus on customer data systems, production infrastructure, emphasize SOC 2 compliance.

- Retail: PCI DSS scope (cardholder data environment), seasonal employee handling, point-of-sale systems.

By regulatory requirements:

- SOX-only: Can focus narrowly on financial systems, quarterly minimum.

- SOX + SOC 2: Need broader scope covering customer data, semi-annual acceptable for non-financial.

- HIPAA: Must include all systems with ePHI access regardless of size.

- Multiple regulations: Use longest retention period and strictest requirements across all.

By technical maturity:

- Low automation: Scope based on what you can manually export—be realistic, commit to expansion timeline.

- Medium automation: SSO-integrated apps quarterly, non-SSO annually until integration complete.

- High automation: Comprehensive scope including shadow IT, shorter review cycles possible.

Key Decision Points

- SSO vs non-SSO apps: Treat differently? If yes, document separate frequencies.

- Service accounts: Include or exclude? Many policies exclude, handle separately via privileged access management.

- Contractor access: In scope or handled via vendor management? Either is fine, must be explicit.

- Development environments: Exclude if no production data, include if production data exists.

Component 2: Roles and Responsibilities

What It Is

This component assigns clear accountability for every aspect of your review program. It defines who owns the policy, who launches reviews, who certifies access, who executes remediations, and who validates compliance.

Using a RACI matrix (Responsible, Accountable, Consulted, Informed) prevents the "everyone's responsibility = no one's responsibility" problem.

Why It Matters

For execution: Reviews fail when ownership is unclear. Managers think IT is handling it. IT thinks Security is handling it. Security thinks Compliance is handling it. Ultimately, nothing happens.

For auditors: They need to know who to interview. "Who ensures reviews complete on time?" "Who validates remediation?" Vague answers create doubt about control effectiveness.

For escalation: When issues arise (missed deadlines, access disputes, technical barriers), clear ownership provides escalation paths. No ownership = no accountability.

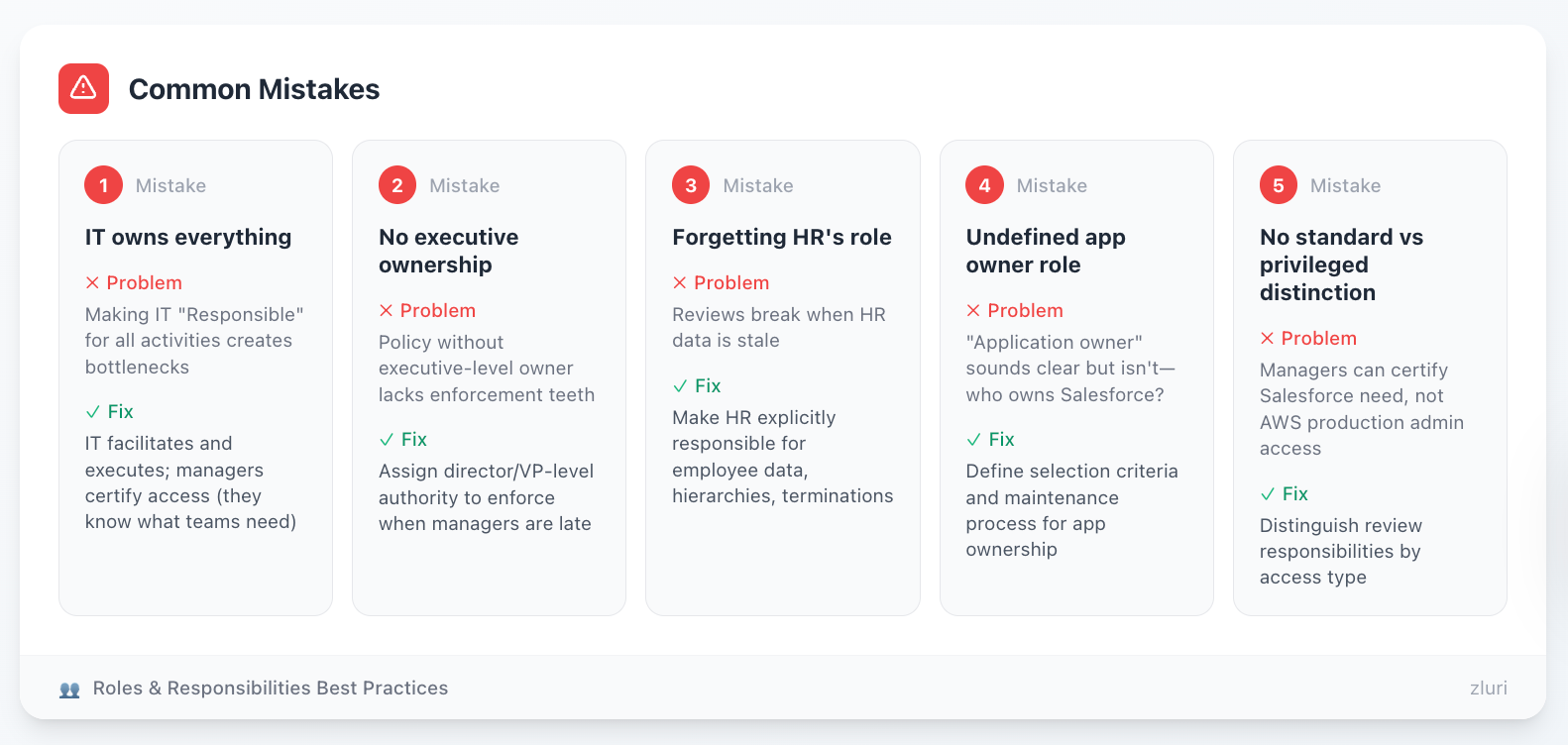

Common Mistakes

Mistake 1: IT owns everything Making IT "Responsible" for all activities creates bottlenecks. IT should facilitate and execute, but managers should certify access (they know what their teams need).

Mistake 2: No executive ownership Policy without executive-level owner lacks enforcement teeth. Who makes managers complete reviews when they're late? Needs director/VP-level authority.

Mistake 3: Forgetting HR's role Reviews break when HR data is stale. Your policy must explicitly make HR responsible for providing current employee data, manager hierarchies, and termination notifications.

Mistake 4: Undefined app owner role "Application owner" sounds clear but isn't. Who owns Salesforce—Sales VP, Salesforce Admin, IT? Your policy must define selection criteria and maintenance process.

Mistake 5: No distinction between standard and privileged access Managers can certify whether their team needs Salesforce. They can't certify whether someone needs AWS production admin access. Distinguish review responsibilities by access type.

Customization Factors

By organizational structure:

- Centralized IT: IT Operations owns more of the process, coordinates tightly with Security.

- Decentralized IT: Business unit IT teams share ownership, requires clear boundaries.

- Outsourced IT: Must define vendor responsibilities in policy, maintain oversight accountability internally.

By company maturity:

- Startup (<50 people): Combine roles—IT Director might be policy owner + administrator + infrastructure.

- Growth stage (50-500): Separate IT Operations, Security, Compliance roles but individuals might wear multiple hats.

- Established (500+): Fully separated roles with dedicated teams.

By review model:

- Manager-based: Managers are primary certification owners, HR role is critical for hierarchy accuracy.

- App owner-based: App owners dominate, need clear ownership register and succession planning.

- Hybrid: Both managers and app owners require clear criteria for which reviews go to whom.

By compliance requirements:

- SOX: Requires separate review and approval (maker-checker), often IT proposes remediations, Security/Compliance approves.

- SOC 2: Emphasizes segregation of duties, policy must show different people execute reviews vs remediations.

- HIPAA: Requires designated Privacy Officer involvement in high-risk access decisions.

Key Decision Points

- Who owns the policy itself? CISO, VP IT, Compliance Director? Must have authority to enforce across the organization.

- Who can approve exceptions? Same as policy owner or separate exception authority?

- Do managers review admin access? Or escalate all admin to security/app owners?

- Who validates remediation completion? IT self-validates or independent verification by Security/Compliance?

- What happens to orphaned reviews? When a reviewer leaves the company or an employee has no manager, who takes over?

Component 3: Review Frequency and Triggers

What It Is

This component establishes when reviews happen—both scheduled (quarterly, semi-annual, annual) and event-driven (terminations, role changes, security incidents).

It creates predictable rhythms (Q1, Q2, Q3, Q4) and defines which events trigger unscheduled reviews outside the regular cadence.

Why It Matters

For compliance: Most frameworks specify minimum frequency. SOX requires quarterly. PCI DSS requires quarterly. Your policy must meet these minimums for in-scope systems.

For resource planning: Knowing reviews happen in the first week of January/April/July/October lets IT staff their team accordingly, preventing "surprise" reviews that disrupt other work.

For risk reduction: Event-driven triggers (terminations, security incidents) prevent waiting 3 months to review access for departed employees or compromised accounts.

Common Mistakes

Mistake 1: One-size-fits-all frequency "All systems reviewed quarterly" sounds good but wastes resources. Your internal wiki doesn't need quarterly review. Risk-based tiering (critical quarterly, standard semi-annual, low-risk annual) is smarter.

Mistake 2: Vague language "Regular reviews," "periodic reviews," "as needed"—all fail audit. State specific timeframes: "quarterly" means every 90 days, not "a few times a year."

Mistake 3: No event triggers Waiting for scheduled review to remove terminated employee access creates 0-90 day exposure window. Policy must require immediate review upon termination.

Mistake 4: Unrealistic commitments Promising monthly reviews when you can barely complete quarterly creates instant non-compliance. Start with achievable frequency, tighten as automation improves.

Mistake 5: No trigger definitions "Review access upon role change" sounds clear. Does "role change" mean promotion? Lateral move? Department transfer? Change in job title only? Define explicitly.

Customization Factors

By system risk/sensitivity:

- Tier 1 (Critical): Financial systems, production databases, customer PII → Quarterly minimum

- Tier 2 (Important): Standard business apps, departmental tools → Semi-annual

- Tier 3 (Low-risk): Internal wikis, learning platforms, <10 users → Annual

By access type:

- Privileged/admin access: Quarterly regardless of system (admin access is always high-risk)

- Standard user access: Varies by system tier

- Read-only access to low-sensitivity data: Annual or bi-annual sufficient

By regulatory driver:

- SOX systems: Quarterly mandatory, no exceptions

- PCI DSS cardholder data: Quarterly mandatory

- HIPAA ePHI systems: Quarterly recommended, semi-annual minimum

- SOC 2: Semi-annual acceptable for standard systems, quarterly for critical

By organizational capacity:

- Limited IT resources: Start with annual for most systems, quarterly only for compliance-required.

- Growing automation: Expand quarterly scope as discovery and remediation automate.

- Mature program: Monthly reviews for highest-risk become feasible.

By company dynamics:

- High turnover: More frequent reviews or stronger termination triggers

- Seasonal business: Adjust review timing around busy periods (don't launch review during retail holiday season)

- M&A activity: Add trigger for system acquisition, require review within 60-90 days of integration

Key Decision Points

- Align to fiscal or calendar quarters? Either works, but fiscal alignment is often easier for reporting.

- Define "terminated": Last day of work or last day on payroll? (These can differ by weeks)

- Role change within 5 days: Is this 5 business days or calendar days?

- Extended leave threshold: 30 days? 60 days? 90 days? When does leave trigger review?

- Security incident scope: Which incidents trigger review—all or only access-related?

Component 4: Review Scope and Least Privilege Requirements

What It Is

This component defines what gets reviewed during each cycle and how reviewers evaluate whether access is appropriate.

It specifies what data reviewers see (user, app, role, last login, etc.), what decisions they can make (approve, deny, modify, escalate), and what criteria determine "appropriate access" (the least privilege principle).

Why It Matters

For decision quality: Reviewers with rich context (last login, role fit, peer comparison) make better decisions than reviewers seeing only "John Smith - Salesforce - User."

For consistency: Without defined criteria, every reviewer interprets "appropriate" differently. One approves anything used in the past year. Another requires explicit job description mention. Documented criteria create shared standards.

For audit defense: When the auditor asks "why does this person have admin access?", you need documented criteria that was applied during review. "It seemed fine" isn't adequate. "Policy requires admin access for on-call engineers, this person is on-call rotation" is defensible.

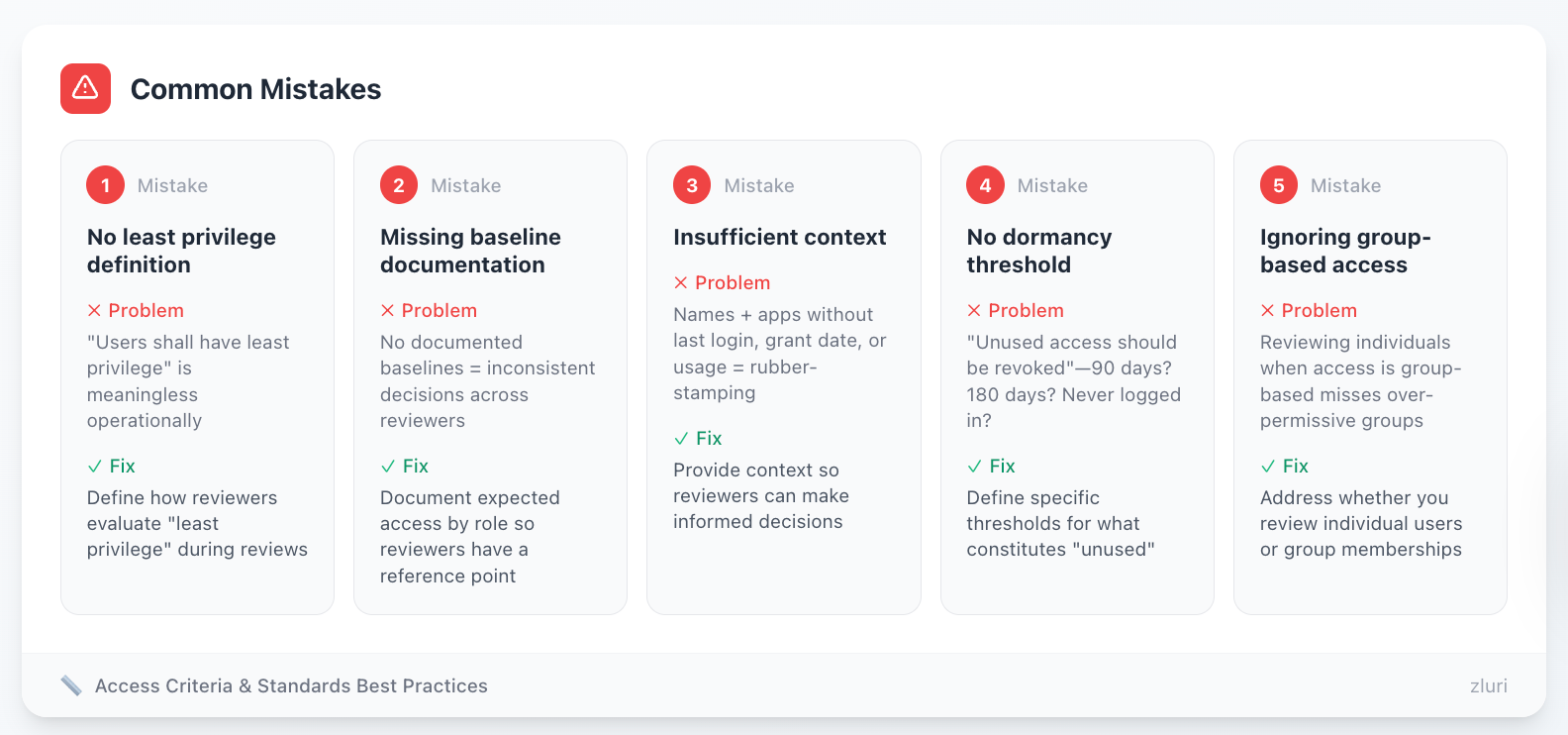

Common Mistakes

Mistake 1: No least privilege definition "Users shall have least privilege" is meaningless without defining what that means operationally. How do reviewers evaluate "least privilege" during reviews?

Mistake 2: Missing baseline documentation Expecting reviewers to know appropriate access for every role without documented baselines creates inconsistency. Marketing Manager at Company A gets Salesforce admin access. Marketing Manager at Company B gets standard user access. Which is right?

Mistake 3: Insufficient context Giving reviewers list of names and apps without last login date, access grant date, or usage frequency leads to rubber-stamping. They can't make informed decisions without context.

Mistake 4: No dormancy threshold "Unused access should be revoked" without defining "unused"—90 days? 180 days? Never logged in?—creates arbitrary decisions.

Mistake 5: Ignoring group-based access If you grant access via SSO groups, policy must address whether you review individual users or group memberships. Reviewing individuals when access is group-based misses over-permissive groups.

Customization Factors

By access provisioning model:

- Individual provisioning: Review user-by-user, app-by-app (traditional model)

- Group-based provisioning: Review group memberships and group entitlements (modern SSO model)

- Role-based provisioning: Review role assignments and role definitions (enterprise model)

By organizational maturity:

- Ad-hoc access management: Start with simple criteria (employed + used recently = approve). Build sophistication over time.

- Documented roles: Can use role baselines as evaluation criteria if they exist.

- Mature RBAC: Can leverage existing role definitions, focus review on exceptions and privilege creep.

By reviewer sophistication:

- First-time reviewers: Need very explicit criteria, decision trees, AI recommendations.

- Experienced reviewers: Can handle more nuanced evaluation, fewer guard rails needed.

- Mixed experience: Provide both simple guidelines and advanced criteria, let reviewers self-select appropriate levels.

By app complexity:

- Simple apps (binary access): Either have access or don't, review is straightforward.

- Permission-level complexity: Many permission options within the app (viewer, editor, admin, owner), review must evaluate permission level not just access.

- Inherited access: Access via group membership, review must consider both individual and group.

Key Decision Points

- Dormancy threshold: 60, 90, or 120 days? Consider typical usage patterns for least-used apps.

- User-based vs group-based: Which review model fits your access provisioning?

- Modification option: Allow reviewers to downgrade permission levels or only approve/deny?

- Peer comparison: Show reviewers what access others in similar roles have?

- AI recommendations: Use platform intelligence to flag anomalies or let reviewers judge independently?

Component 5: Remediation Requirements

What It Is

This component defines how access marked for removal actually gets removed—the workflow from certification decision to technical execution to validation.

It establishes remediation SLAs (how quickly), verification requirements (proof it worked), and tracking mechanisms (audit trail of actions).

Why It Matters

For risk reduction: Identifying inappropriate access but not removing it accomplishes nothing. Access review without remediation is a security illusion.

For audit compliance: Auditors don't just want to see review decisions—they want proof those decisions were executed. "We decided to revoke" without evidence of revocation fails the audit.

For accountability: SLAs create forcing functions. Without deadlines, remediations languish in backlogs for months. With SLAs, delayed remediations escalate to management automatically.

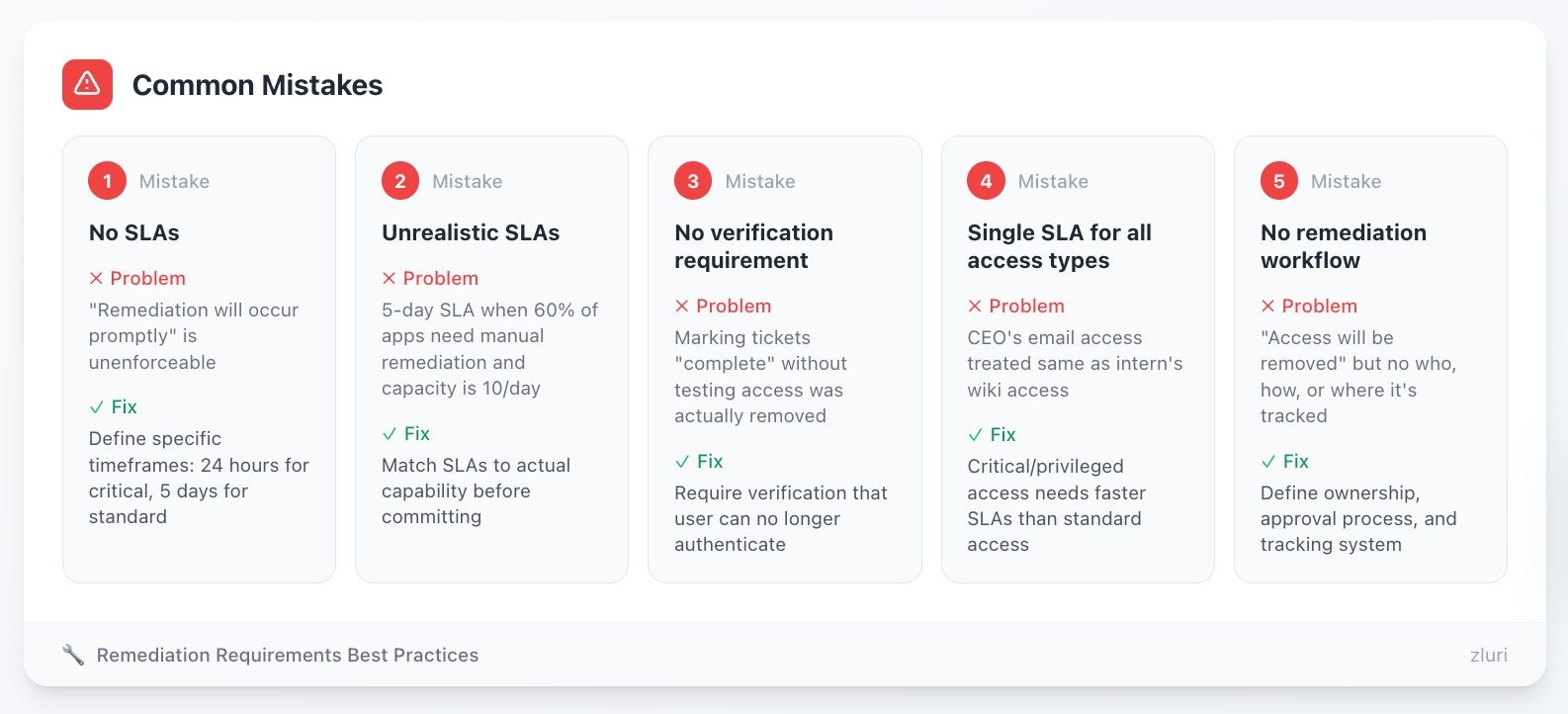

Common Mistakes

Mistake 1: No SLAs "Remediation will occur promptly" is unenforceable. Define specific timeframes: 24 hours for critical, 5 days for standard.

Mistake 2: Unrealistic SLAs Committing to 5-day SLA when 60% of apps require manual remediation and your team capacity is 10 remediations/day creates instant failure. Match SLAs to actual capability.

Mistake 3: No verification requirement Marking tickets "complete" without testing that access was actually removed. Users might still authenticate successfully despite "completed" remediation.

Mistake 4: Single SLA for all access types Treating "remove CEO's email access" the same as "remove former intern's access to internal wiki" doesn't match risk. Critical/privileged access needs faster SLAs.

Mistake 5: No remediation workflow Policy says "access will be removed" but doesn't define who does it, how it's approved, or where it's tracked. Remediations happen ad-hoc or not at all.

Customization Factors

By automation level:

- High automation (80%+ apps): Aggressive SLAs possible—24 hours critical, 3 days standard

- Medium automation (50-80%): Moderate SLAs—24 hours critical, 5 days standard, 10 days manual

- Low automation (<50%): Conservative SLAs—24 hours critical (non-negotiable), 10 days standard, 15 days manual

By app architecture:

- SSO-integrated: Fast remediation via SSO API, can commit to short SLAs

- SCIM-provisioned: Automatic sync after SSO removal, slightly longer due to sync delay

- Legacy/manual: Requires logging into each app admin panel, longer SLAs justified

- Vendor-managed: Requires support tickets, can take 5-10 business days, document this reality

By access criticality:

- Privileged/admin access: 24 hours maximum (sometimes 4 hours for highest-risk)

- Standard business app access: 5 business days typical

- Low-sensitivity read-only: 10 business days acceptable

- Emergency (compromised account): Immediate (1 hour or less)

By organizational size:

- Small (<200 employees): Fewer remediations per cycle, manual remediation manageable

- Mid-market (200-5000): Volume requires some automation, hybrid manual/auto approach

- Enterprise (5000+): Manual remediation at scale unsustainable, automation mandatory

Key Decision Points

- When does SLA clock start? Review decision timestamp or remediation approval timestamp?

- Verification sampling vs 100%? Sample 10% or verify every remediation?

- Critical access definition: Which access types qualify for 24-hour SLA?

- Failed remediation handling: If app API fails, what's the compensating control until manual remediation?

- Bulk remediation approval: Does IT execute all remediations or require batch approval from Security?

Component 6: Documentation and Evidence Retention

What It Is

This component specifies what records must be maintained, in what format, stored where, accessible by whom, and retained for how long.

It defines evidence categories (review planning, execution, remediation, reporting), documentation formats (PDF, CSV, screenshots, API logs), and retention periods (7 years for SOX, 6 years for HIPAA, etc.).

Why It Matters

For audits: Auditors require evidence packages. Without documented requirements, teams compile evidence ad-hoc during audits—missing items, inconsistent formats, gaps in trail.

For legal/regulatory: Retention requirements are legal obligations. Deleting SOX evidence after 5 years when SEC requires 7 creates regulatory violations.

For continuous improvement: Historical evidence enables analysis—"our completion rate improved from 65% to 92% over four quarters." Can't measure improvement without preserved evidence.

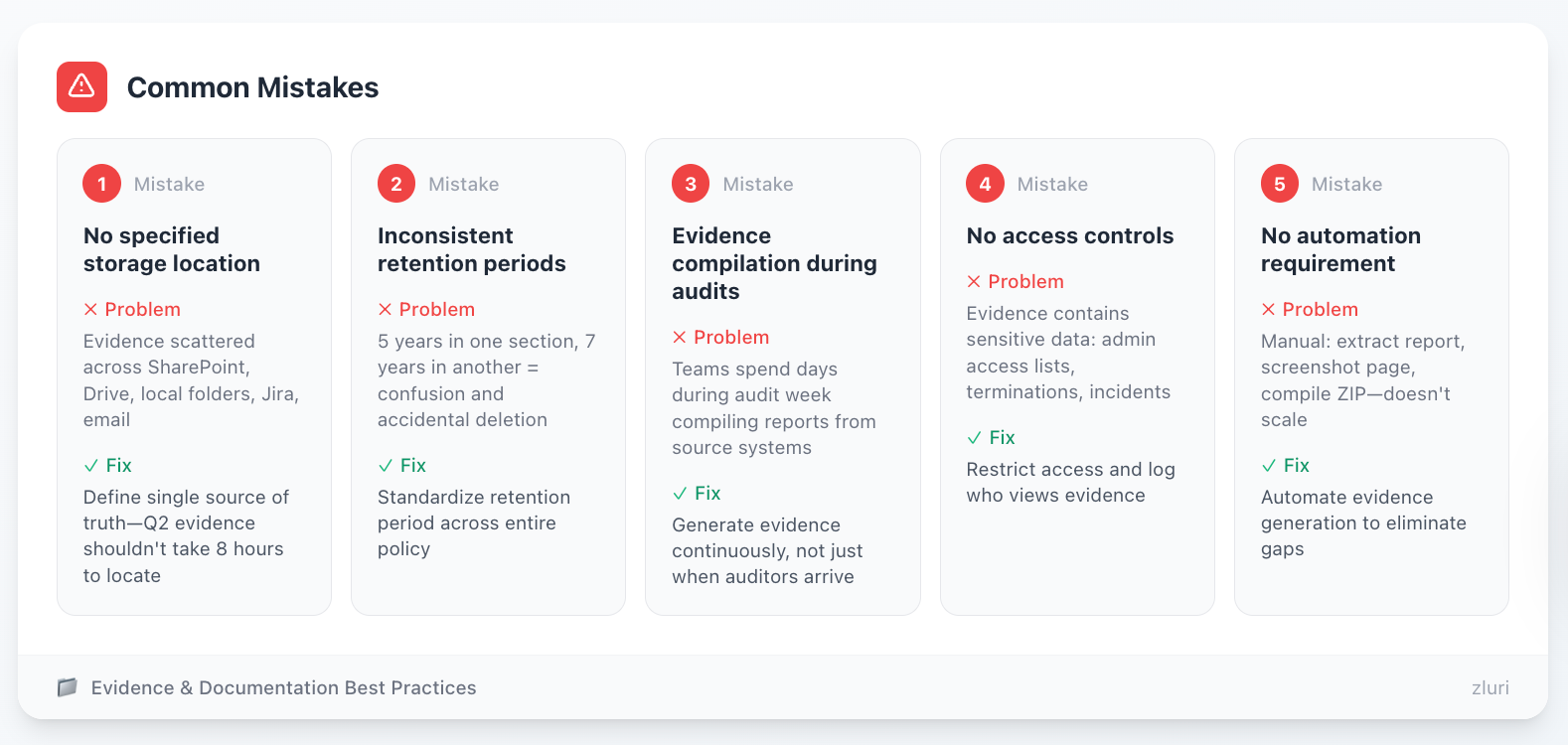

Common Mistakes

Mistake 1: No specified storage location Policy says "evidence will be maintained" without defining where. Teams scatter evidence across SharePoint, Google Drive, local folders, Jira, email. Auditors ask for Q2 evidence, which takes 8 hours to locate.

Mistake 2: Inconsistent retention periods Different parts of policy reference different retention (5 years in one section, 7 years in another). Creates confusion and potential deletion of required evidence.

Mistake 3: Evidence compilation during audits Waiting until audit to organize evidence. Teams spend days during audit week compiling reports from source systems instead of generating continuously.

Mistake 4: No access controls Evidence contains sensitive data (who has admin access, termination details, security incidents). Policy must restrict access and log who views evidence.

Mistake 5: No automation requirement Policy describes manual evidence compilation (extract this report, screenshot this page, compile into ZIP). Manual approaches don't scale and create gaps.

Customization Factors

By regulatory requirements:

- SOX: 7 years retention mandatory (SEC requirement)

- HIPAA: 6 years retention minimum

- SOC 2: Duration of audit period + 7 years (auditors may request historical evidence)

- ISO 27001: Per organization's record retention policy

- Multiple regulations: Use longest retention period to simplify

By company size:

- Small (<200 employees): Manual evidence compilation acceptable, specify folder structure and naming conventions

- Mid-market (200-5000): Semi-automated—platform generates reports, humans organize into evidence packages

- Enterprise (5000+): Fully automated evidence generation and storage, no manual compilation

By audit frequency:

- Annual audit cycle: Can batch evidence quarterly, organize during Q4 prep

- Continuous auditing: Must maintain audit-ready evidence continuously, no post-processing

- Multiple auditors: Different auditors want different formats, may need multiple evidence packages per cycle

By tooling maturity:

- Spreadsheet-based: Document manual evidence process in detail (which reports, which screenshots, naming conventions)

- Basic platform: Some automation but gaps remain, document hybrid process

- Advanced platform: Fully automated, policy just references platform's evidence repository

Key Decision Points

- Where is evidence stored? Specific SharePoint path, Google Drive folder, compliance platform?

- Who has access? Internal audit, Compliance, Security, CISO—anyone else?

- How long after the review cycle? Compile evidence immediately or within 30 days?

- What happens to old evidence? After retention period, deleted manually or auto-archived?

- Backup requirements? Primary storage only or replicated to secondary location?

Component 7: Exceptions and Escalations

What It Is

This component handles edge cases that don't fit standard rules—approving exceptions to policy requirements, escalating missed deadlines, resolving disputes about access appropriateness.

It defines exception approval authority, time-bound exception periods, escalation paths for overdue reviews and delayed remediations, and dispute resolution mechanisms.

Why It Matters

For pragmatism: Real-world scenarios break policies. For example, a contractor needs temporary admin access for 3-week migration. Legacy apps can't integrate with SSO for 6 months. Without the exception process, teams violate policy or block legitimate business needs.

For enforcement: Clear escalation paths create accountability. "Overdue review escalates to manager, then director, then CISO" prevents reviews from languishing incomplete.

For conflict resolution: Managers and Security disagree about access appropriateness. App owners and Compliance dispute remediation timelines. A documented resolution process prevents these becoming political battles.

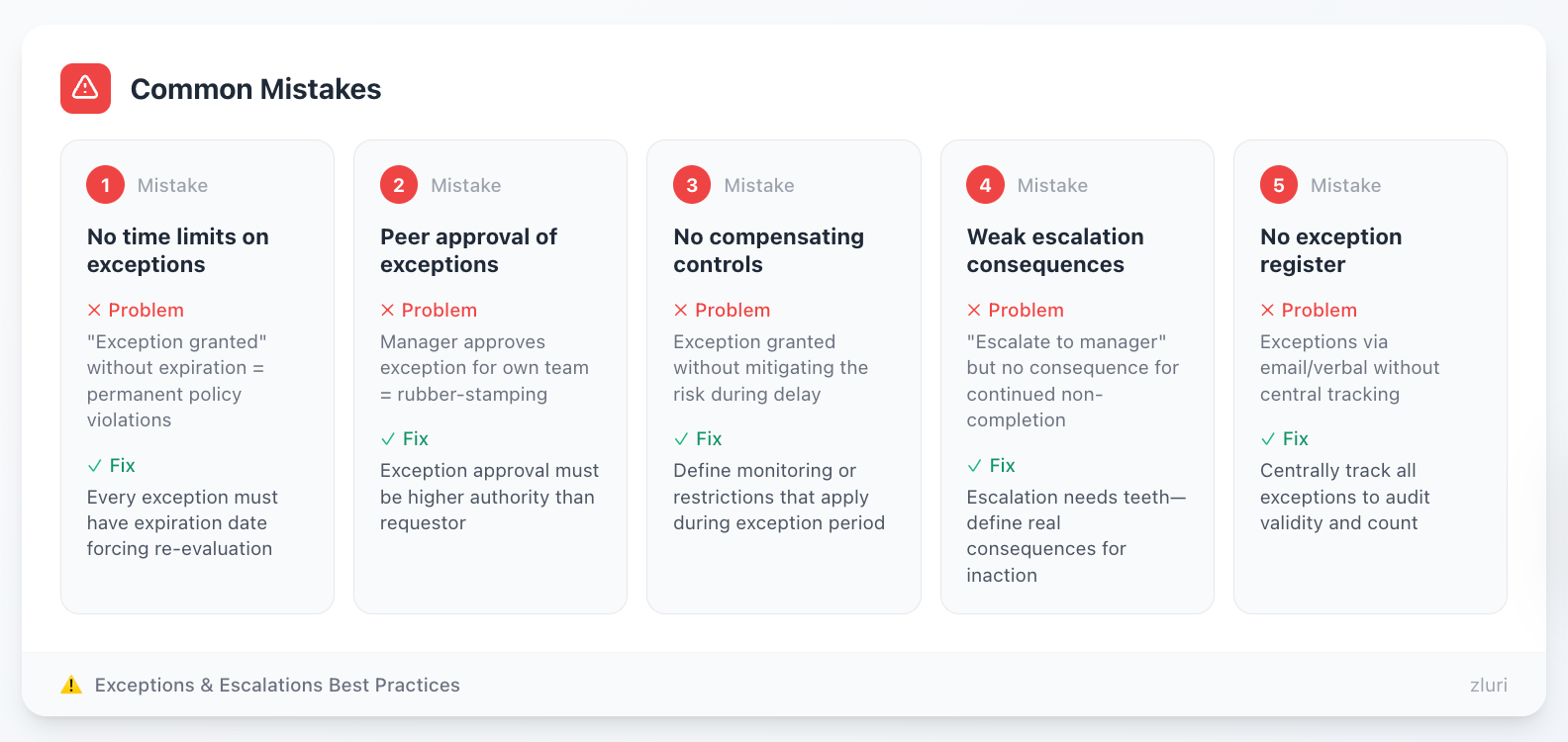

Common Mistakes

Mistake 1: No time limits on exceptions "Exception granted" without expiration creates permanent policy violations. Every exception must have an expiration date forcing re-evaluation.

Mistake 2: Peer approval of exceptions Manager approves exception for their own team. Creates rubber-stamping. Exception approval must be higher authority than requestor.

Mistake 3: No compensating controls Granting exception without requiring compensating controls to mitigate risk. If remediation is delayed 30 days, what monitoring or restrictions apply during delay?

Mistake 4: Weak escalation consequences "Overdue reviews escalate to manager" but no consequence for continued non-completion. Escalation without teeth becomes nagging without action.

Mistake 5: No exception register Exceptions granted verbally or via email without central tracking. Impossible to audit how many exceptions exist or whether they're still valid.

Customization Factors

By organizational culture:

- Risk-averse: Exceptions require CISO/CFO approval, quarterly review of all exceptions, sunset after 90 days maximum

- Pragmatic: Exceptions approved by directors, annual review, 12-month maximum duration

- Growth-stage chaos: Liberal exception process while building controls, tighten as organization matures

By compliance requirements:

- SOX environment: Exceptions require documented risk assessment, often require Audit Committee notification for significant exceptions

- SOC 2: Exception log becomes part of audit evidence, must show exceptions were managed

- Less regulated: More flexibility but still need documentation for internal accountability

By company size:

- Small (<200 employees): CEO/CFO might approve exceptions directly, informal but documented process

- Mid-market (200-5000): VP-level approval, quarterly exception review in leadership meetings

- Enterprise (5000+): Formal exception committee, risk scoring, compensating control requirements

By escalation urgency:

- Critical access: Auto-disable after deadline for privileged access to financial/production systems

- Standard access: Escalation path (manager → director → VP) without auto-disable

- Low-risk: Email reminders without management escalation

Key Decision Points

- Who can approve exceptions? CISO only, or department VPs for their areas?

- Maximum exception duration: 90 days, 6 months, 12 months?

- Auto-disable threshold: What access types warrant automatic disablement if review is not completed?

- Dispute resolution authority: CISO decides or escalates further to CFO/CRO?

- Exception renewal process: Automatic renewal allowed or must re-justify?

Component 8: Policy Governance

What It Is

This component defines how the policy itself gets maintained—annual review requirements, update triggers, stakeholder approval process, version control, and training requirements.

It treats the policy as a living document that evolves with organizational changes, regulatory updates, and process improvements.

Why It Matters

For relevance: Policies written in 2020 don't account for 2024 reality—cloud migrations, new apps, organizational restructuring, changed regulations. Without governance, policies become obsolete.

For compliance: Auditors check policy review dates. Policy last reviewed 3 years ago raises questions about whether it's still followed. Annual review demonstrates active management.

For adoption: Training requirements ensure stakeholders understand their responsibilities. Certification owners can't follow policy they've never read.

Common Mistakes

Mistake 1: No review cadence Policy written once, never updated. Becomes disconnected from actual practices over time.

Mistake 2: Reactive updates only Only updating after audit findings. Proactive annual review prevents problems before auditors find them.

Mistake 3: No version control Policy updates without maintaining version history. Can't demonstrate how policy evolved or why changes were made.

Mistake 4: Skip training Policy updated but stakeholders not informed. Reviewers follow outdated procedures because they weren't trained on changes.

Mistake 5: No impact assessment Policy changed without considering operational impact. "We updated remediation SLA from 10 days to 5 days" without validating IT can meet new SLA.

Customization Factors

By organizational maturity:

- Startup: Policy reviewed annually or when major changes occur, minimal formality

- Growth stage: Quarterly policy review for first 2 years while building program, annual after stabilization

- Established: Annual review standard, triggered updates for significant changes

By regulatory environment:

- Highly regulated: Policy changes require board approval, formal change management, legal review

- Moderately regulated: VP-level approval sufficient, legal review for significant changes

- Less regulated: Policy owner approval adequate, lightweight change process

By change frequency:

- Stable environment: Annual review adequate

- Rapid growth: Quarterly review recommended as organization scales

- M&A activity: Policy review required within 90 days of acquisition

- Major technology changes: Trigger review when implementing new SSO, moving to cloud, etc.

By training burden:

- Small reviewer population (<50): Live training sessions feasible

- Large reviewer population (500+): Self-paced training modules required, live sessions impractical

- High turnover: On-demand training library for continuous onboarding

Key Decision Points

- Who approves policy updates? Policy owner alone or requires executive/board approval?

- Material vs non-material changes: What constitutes "material" requiring full stakeholder review vs minor corrections?

- Training trigger: Required before first review only or refresher training annually?

- Version control location: SharePoint, Google Drive, compliance platform, wiki?

- Annual review timing: Calendar year, fiscal year, or anniversary of policy creation?

How to Use These Components

Now that you understand all 8 components, here's how to build your policy:

Step 1: Assess Your Current State

For each component, evaluate:

- Do we do this today? (Existing practice)

- Can we do this tomorrow? (Immediate capability)

- What must we build? (Requires investment)

Be honest: Write policy matching current capability + committed roadmap, not aspirational future state.

Step 2: Map to Your Regulations

Identify which compliance frameworks apply:

- SOX → Emphasize financial systems, quarterly reviews, segregation of duties

- PCI DSS → Scope cardholder data environment, quarterly reviews mandatory

- HIPAA → Include ePHI systems, role-based access, minimum necessary

- SOC 2 → Broader scope including customer data, semi-annual acceptable

- ISO 27001 → Annual minimum, integrate with broader ISMS

Step 3: Customize by Your Context

Apply customization factors discussed for each component:

- Company size (small vs mid-market vs enterprise)

- Industry requirements (financial vs healthcare vs tech)

- Technical maturity (manual vs automated)

- Organizational structure (centralized vs decentralized)

Step 4: Use the Template

We've created a ready-to-use policy template incorporating all 8 components. Download it, customize the [bracketed] sections using the guidance above, and you'll have an audit-ready policy.

The template includes:

- All 8 components with copy-paste language

- Customization notes for key decisions

- Compliance mapping by regulation

- Sample RACI matrix

- Version control template

Step 5: Get Stakeholder Buy-In

Before finalizing:

- IT Operations: Can we execute this? Do SLAs match our capacity?

- Security: Does this adequately reduce risk?

- Compliance: Does this meet audit requirements?

- Business managers: Is reviewer burden reasonable?

Incorporate feedback, adjust components as needed, secure approval.

Step 6: Implement Before Auditing

Don't hand auditors a beautiful policy you've never followed. Minimum:

- Execute one complete review cycle using the policy

- Generate evidence per policy requirements

- Identify gaps between policy and practice

- Update policy to match reality

Auditors respect "here's our policy, we've run it once, we found these gaps and adjusted" far more than "here's our perfect policy we've never tested."

Common Cross-Component Mistakes

Beyond component-specific mistakes, watch for these system-level errors:

Mistake 1: Inconsistent Scope Across Components

Component 1 says "all applications." Component 3 says "quarterly reviews of critical applications." Component 6 says "evidence for financial systems."

Which is the real scope? Auditors notice inconsistencies. Ensure scope definition in Component 1 cascades consistently through all other components.

Mistake 2: Mismatched SLAs and Automation

Component 5 commits to 5-day remediation SLA. But Component 1 scope includes 40 manual-only applications requiring 15+ minutes each to remediate.

Math: 40 apps × 10 revocations per cycle × 15 minutes = 100 hours of work. Can't complete in 5 days without full-time dedicated staff.

Ensure remediation SLAs match automation level and IT capacity.

Mistake 3: Evidence Requirements Without Storage Plan

Component 6 requires detailed evidence categories. Component 8 has no documentation section for evidence location.

Result: Evidence generated but scattered across systems, difficult to locate during audit.

Ensure evidence requirements in Component 6 align with storage plan in Component 8.

Mistake 4: Roles Without Authority

Component 2 makes IT Operations "responsible" for ensuring reviews complete on time. Component 7 has no escalation path giving IT Operations authority to escalate to directors.

Result: IT Operations can monitor but can't enforce. Reviews languish.

Ensure roles in Component 2 have enforcement mechanisms in Component 7.

Mistake 5: Training Requirements Without Content

Component 8 requires annual training. Component 2 describes complex responsibilities for certification owners.

But policy provides no training materials or decision criteria to train people on.

Ensure training requirements in Component 8 have supporting content (decision frameworks from Component 4, workflows from Component 5).

From Policy to Practice

Your documented policy satisfies auditors—it's the execution that reduces risk.

The best policies are ones that:

- Match your current capabilities (not aspirational ones)

- Define clear, measurable requirements (not vague language)

- Specify who does what (explicit ownership)

- Establish realistic timelines (achievable SLAs)

- Document what evidence you'll generate (not what you wish you could generate)

We recommend starting by documenting what you actually do today—then evolving the policy toward what you should be doing.

If you're already doing reviews but lack formal documentation, capture your existing workflow in policy format and refine from there.

Your goal isn't a perfect policy on day one. Your goal is a documented, repeatable framework that you can continuously improve.

Next Steps

See automation in action: How platforms automate evidence generation → Book a Demo

Disclaimer: The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. It does not constitute legal, regulatory, or compliance advice. While we strive to provide accurate and up-to-date information about access review policies and compliance frameworks (SOX, SOC 2, HIPAA, PCI DSS, ISO 27001, GDPR, etc.), regulations and requirements vary by jurisdiction, industry, and organization. The specific requirements that apply to your organization depend on your unique circumstances.

This article should not be used as a substitute for professional legal counsel or qualified compliance advisors. Before implementing any access review policy, we strongly recommend consulting with your legal team, compliance officers, or qualified professionals who can assess your specific regulatory obligations and organizational requirements. The sample policy language, templates, and recommendations provided are starting points for customization—not ready-to-use legal documents. Your organization is responsible for ensuring any policy meets your specific legal, regulatory, and business requirements.

.png)

.svg)